Some people make the mistake of thinking that Kingsmere, the Gatineau Park location of the Mackenzie King estate, is named after William Lyon Mackenzie King. In fact Kingsmere is named for King Mountain nearby, which had gotten its name before Mackenzie King ever showed his face in the Gatineaus in 1900.

But King Mountain is famous for a third King. William Fredrick King was head of the Geodetic Survey of Canada and used King Mountain as the starting point for the entire network of survey triangulation points for the entire country beginning in 1905.

Here’s the story:

One popular trail in Gatineau Park is the King Mountain trail accessible from the Champlain Parkway with a deceptively pastoral looking parking lot. Walk the circular trail though, and you’ll find lots of up and down amply rewarded by some of the best lookout views in the park.

It was King Mountain that William Lyon Mackenzie King first visited before he began amassing his estate at Kingsmere some years later. But King Mountain was already named before William Lyon Mackenzie King ever showed up and even more curious is that as you walk the King Mountain trail you’ll pass a monument that wouldn’t be there had it not been for a third King, William Frederick King who in 1905 chose the place for the very first geodetic triangulation point in Canada.

You’ve seen survey crews before, setting up their tripods and marking out exactly where a road will go or perhaps the edge of a property line. These crews make careful measurements so that people can tell exactly where a point is on the earth’s surface; so your fence isn’t on my land for instance. The key to this accuracy is that survey crews measure where a point is relative to somewhere else that they already know. Until King Mountain in 1905 there was no place in Canada for surveyors to start from.

William Frederick King changed all that when he had his guys build a small tower on King Mountain. From there he could see his office on Carling Avenue (the Dominion Observatory) and triangulate between it and sites in Masham, Wakefield and Buckingham. Eventually from there points for triangulation spread all across Canada.

This was an important enough achievement that in 1929 King Mountain was designated a National Historic Site and a monument was built to celebrate the fact. So, from a Canadian surveyor’s perspective, King Mountain is the centre of the universe. Because Parks Canada administers the list of National Historic Sites but doesn’t administer the site itself, it is a little difficult to find reference to King Mountain on the Parks Canada website; this unfortunately is true of many many other historic sites.

This was an important enough achievement that in 1929 King Mountain was designated a National Historic Site and a monument was built to celebrate the fact. So, from a Canadian surveyor’s perspective, King Mountain is the centre of the universe. Because Parks Canada administers the list of National Historic Sites but doesn’t administer the site itself, it is a little difficult to find reference to King Mountain on the Parks Canada website; this unfortunately is true of many many other historic sites.

Here’s what the NCC Plaque says (I think it’s a little simplisitc, don’t you?)

A Shrine to Surveying in Canada

From here you have the best view of the entire region. If you need convincing, just read the inscription on the monument erected on this site!

This unobstructed view of the whole area prompted the installation of Canada’s first triangulation point, on the summit of King Mountain. At a glance you can see the cities of Gatineau, Hull, Aylmer, and Ottawa and it’s suburbs.

Here’s what the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada says on its plaque

Geodetic Survey of Canada

By the accurate determination of points on the earth’s surface, a geodetic survey establishes a framework upon which to base detailed surveys. Although geodetic work was carried out sporadically in Canada during the late 19th century, a systematic programme was not begun until July 1905, when the first triangulation station was erected atop King Mountain by a field party under the direction of C. A. Bigger, assistant to Dominion Astronomer W. F. King, who was in charge of the operation. In April 1909 the Geodetic Survey of Canada was created by order-in-council and King was appointed Superintendent.

And from their website: Date Designated: 1929, Plaque status: Plaqued in 1930

The Ottawa Citizenc overed the unveiling of the monument in the news of September 2, 1931

Unveiling Tablet To First Geodetic Survey in Canada

Aylmer East Branch Quebec Women’s Institute Arranging Ceremony for Saturday Afternoon

Of Particular local interest is the ceremony being arranged for Saturday September 5 by the Aylmer East Branch of the Quebec Women’s Institute in connection with the unveiling of the memorial on King Mountatin to mark the first geodetic survey station in the Dominion.

This memorial, taking the form of a bronze tablet mounted on a rubble-stone cairn, was erected last year by the department of the Interior on the recommendation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. At this point 1,125 feet above sea level, was pmmenced in 1905 the triangular system of the Geodetic Survey of Canada, forming the basis of surveys for all purpose, topographical, engineering and cadastral, under the direction of the late Dr. W. F. King C.M.G.

The unveiling ceremonies will be held on the property of Michael P. Mulvihill, Mountain road, who donated the site for the memorial, and will commence at 2:30 p.m., easter daylight time.

The program follows:

Welcome address F. Ferris, mayor, South Hull; invocation, Rev. Father Stanton, Chelsea; unveiling, Mrs. G. E. Radmore, president, Aylmer East Institute; Nationial Anthem; addresses by Brig.-Gen E.A. Cruikshank, chairman, Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada; Mrs’ Laura Rose Stephen, Ottawa and Mr. Noel J. Ogilvie, director, Geodetic Survey of Canada.

A more complete history of the Geodetic Survey can be found here.

This feature of King Mountain is also the subject of an article by Duncan Marshall in Volume 36 of Up The Gatineau, the newsleter of the Gatineau Valley Historical Society.

]]>Gatineau Park was founded in large part based on its role for recreation. The more recent emphasis on conservation highlights concerns that park users could with time love the place to death. That was part of the message behind the Recreation Services Plan consultations in the fall of 2009. People who can’t read a map are wandering through the woods using the GPS in their iPhone. People who can’t ski are strapping on snowshoes. More people means more pressure on the park. More nervous animals avoiding places they used to frequent, more shoes scrunching foliage and dislodging pebbles. Gatineau Park can’t be all things to all people and so there are going to have to be some limitations.

At the end of June 2010 the NCC posted a report on the fall consultations. Although the report claims that the consultation clarified how the Plan should look, saying “a majority … were in agreement with the proposed assessment, vision and mission,” in only one case did those who agreed or strongly agreed amount to 50%, in all other cases support was lower.

Click graphs to enlarge.

I think the reason the results were so muddy was that the information that people were asked to comment on was not very specific; it was all very conceptual and didn’t identify how recreation might be restricted or controlled.

At the time the mood appeared to be “it’s all right as far as it goes” but the phrase “the devil is in the details” came up with enough regularity that it is highlighted in the report.

From the material presented so far it’s hard to know what the final Recreational Services Plan might look like. And yet the intent of the NCC in holding its consultation was stated as

“to ensure participation in [the Plan’s] development by the general public, the users as well as user associations.”

A second round of consultations is planned but only after the NCC has a Plan to show Park users. There doesn’t appear to be any opportunity for consultations that would further refine the plan once users had a chance to see it.

I would suggest that the murkiness of the Plan’s detail so far, combined with its lukewarm support by the user community, would speak to the need for deeper user community involvement before the NCC considers the Plan as finalized.

The recently released consultation report underlines this need when it emphasizes that efforts have to be made to increase the trust between the sports community and Gatineau Park’s management team. The report also noted that user consensus would require more consultation and dialogue, plus partnerships with stakeholders.

Other Points

In addition to the fundamental issues noted above, two specific questions emerge from the report.

- Are park users onside with the NCC or are they not?

- Does intensity matter?

Onside?

With respect to users and the NCC being on the same wavelength, the report contains two seemingly contradictory statements:

- “The consultation … confirmed that Park stakeholders are committed to understanding the issues at hand and to contributing to possible solutions.”

- “A growing number of users who are both more individualistic and less informed on the recreational heritage developed throughout the years, and even less sensitive to the objectives of environmental conservation.”

Although these statements appear contradictory what I think they mean is that on the one hand, those Park users who are engaged enough to participate in the Recreation Services Plan consultation are engaged enough to work with the NCC if they can find a way to do so. On the other hand, there are more and more casual Park users with whom it’s difficult to get engaged and therefore difficult to work with.

From this it seems to me that the value of the NCC working with user organizations and associations is amplified. Get buy-in on the most appropriate ways to enjoy the Park and also promote membership in the clubs and associations that partner to those ends.

Intensity?

With respect to “intensity” the report states:

“Respondents made clear their opposition to select statements such as ‘Intensive recreational activities could be practiced outside the Park’ or ‘Activities having an important impact on the environment could be practices along the Park’s boundaries.’”

As I recall it the statement that caused objection was “intensive sport activities or those requiring advanced techniques or equipment should be controlled” and the objection was specifically that in a paradigm aimed at conservation, the intensity of a sport or it’s requirement for advanced techniques should not be the measure for its restriction or control, rather its environmental impact should be the gage.

I’m not sure if a point has been missed here or not.

]]>It seems that one of the most photographed places in Gatineau Park is the Carbide Willson Ruins. They say that some people like to sunbathe nude there but that isn’t what most photos are about. I guess part of the charm is this mysterious structure in the middle of the wilderness.

Why’s it there?

Carbide Willson was Thomas Leopold Willson. He was nicknamed Carbide Willson because he made a fortune after stumbling across the formula for calcium carbide.

Carbide Willson was Thomas Leopold Willson. He was nicknamed Carbide Willson because he made a fortune after stumbling across the formula for calcium carbide.

I’ll get to why calcium carbide might have made him rich in a moment, but first let me explain my “stumbling across” comment. He had invented an electric arc furnace and was trying to find a use for the thing. He figured he could produce aluminum from bauxite – fail. He tried producing metallic calcium – fail.

You can just see him in your mind’s eye poking whatever material he could lay his hands on into the furnace to try and turn out something useful. One of these tries combined coal tar with lime and produced a weird kind of mineral. These strange gravely bits started to bubble if you got them wet. Even weirder, the gas that was bubbling off them was freaking flammable.

Willson had no idea what this stuff was that he’d produced and so started corresponding with world renowned scientists asking them if they knew. One of these was William Thomson at the University of Glasgow. William Thompson is better remembered as Lord Kelvin, the guy who came up with the idea that things could get so cold that there was an absolute zero degrees.

Willson had no idea what this stuff was that he’d produced and so started corresponding with world renowned scientists asking them if they knew. One of these was William Thomson at the University of Glasgow. William Thompson is better remembered as Lord Kelvin, the guy who came up with the idea that things could get so cold that there was an absolute zero degrees.

Anyway, our Carbide Willson eventually figured out with the help of these experts that the gravel he was producing was calcium carbide and that the gas that was bubbling off the calcium carbide was acetylene.

These days you might hear of acetylene torches that steel workers use to cut metal with those medieval looking wielder’s helmets on. Back before 1900 though, calcium carbide and acetylene had an entirely different use. Those were the days before electric light bulbs. This calcium carbide stuff was really handy for producing light and heat. All you needed to do was keep the stuff dry until you needed to use it.

To use it you dumped it into a special type of canister with an upper and lower compartment. The lower compartment was half full of water and had a pipe running off it to the light fixtures and cooking ring. The calcium carbide gravel crowded down into a kind of funnel with a rubber valve mechanism on it. A few of the chunks of gravel would fall into the water and start to bubble and as the gas pressure increased it would close the rubber valve, preventing more calcium carbide from falling into the water. The lightly pressurized acetylene then flowed out to do its lighting and heating work, releasing pressure and allowing a few more chunks to restart the process.

To use it you dumped it into a special type of canister with an upper and lower compartment. The lower compartment was half full of water and had a pipe running off it to the light fixtures and cooking ring. The calcium carbide gravel crowded down into a kind of funnel with a rubber valve mechanism on it. A few of the chunks of gravel would fall into the water and start to bubble and as the gas pressure increased it would close the rubber valve, preventing more calcium carbide from falling into the water. The lightly pressurized acetylene then flowed out to do its lighting and heating work, releasing pressure and allowing a few more chunks to restart the process.

It was a beautiful system and since everyone had been reading by candle light and sooty coal oil lamps, everyone had to have it; and Thomas Leopold Willson controlled it all.

So that’s how he got rich and that’s why he was called Carbide Willson.

But that’s not what the Willson Ruin is about.

Having made a bundle lighting up the world he thought he had another bright idea; fertilizer. He wanted to corner the world market on chemical fertilizer. By this time he was living in Ottawa in grand style and like so many of the leading citizens wanted to have a cottage.

Cottage might be a misnomer for a place that has eleven bedrooms and seven fireplaces and its own private telephone connection to the outside world. It was his house that later became the government conference centre where the Meech Lake Accord was dreamed up.

Cottage might be a misnomer for a place that has eleven bedrooms and seven fireplaces and its own private telephone connection to the outside world. It was his house that later became the government conference centre where the Meech Lake Accord was dreamed up.

Dispute his success Willson was a bit of a social klutz so he liked his isolated country estate and looked to the water flowing out of Meech Lake as a source of power for an experimental lab he wanted to set up to corner the fertilizer market. There was already a dam there that had once powered a sawmill but Willson had the means and liked to do things big so he rebuilt the dam in concrete and set up his little lab on a scale that looks to us, and must have looked to others at the time, like a full scale industrial installation.

When I say he was a bit of a social klutz I mean that it never seemed to occur to him that it might annoy his neighbours on Meech Lake to have the lake level vary by six feet one way or another based on his need for generating power. There are reports of boathouses disappearing beneath the waves at one moment and then sometime later standing a good walk away from the water’s edge.

So the ruin that are the subject of so many pictures today had nothing to do with calcium carbide except for the fact it was financed by the stuff; and probably lighted by it.

Carbide Willson liked to do things big and he thought he had the means, but in fact he didn’t have the means. In pursuit of his fertilizer dream he was forced to sell his other assets and ended up ruined himself. He died in 1915 of a heart attack while trying to rebuild after bankruptcy.

Photo Credits and other links:

http://mcgoldrick.ca/xc-skiing/carbide-willson/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Willson_Mill_At_Gatineau_Park.jpg

http://rmcguirephoto.com/wordpress/2010/02/06/thomas-carbide-willson-ruins-gatineau-park-quebec/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikealex/3961625681/

http://www.flickriver.com/photos/mikealex/4229030545/

http://www.chesleyhouse.com/Books/MeechRuins.htm

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/1726259

http://www.flickriver.com/photos/richardmcguire/tags/creek/

http://www.trekearth.com/gallery/North_America/Canada/Central/Quebec/Gatineau/photo762514.htm

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikealex/3981761969/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikealex/3982523338/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/digitalslg/4127217436/

http://www.uer.ca/locations/show.asp?locid=21491

http://www.onvertigo.ca/index.php?showimage=123

http://www.onvertigo.ca/archives.php

http://www.flickr.com/photos/s_and_d/2919817761/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rocurti/4018787034/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/digitalslg/4534788388/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/inottawa/3437647900/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/aylmerqc/266595445/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kadacat/1508366545/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/aylmerqc/1538783402/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kadacat/1555694754/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/haofeng/3993881961/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/haofeng/3949490078/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kadacat/1573770616/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kadacat/1519733198/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikealex/4534127953/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikealex/4229030545/

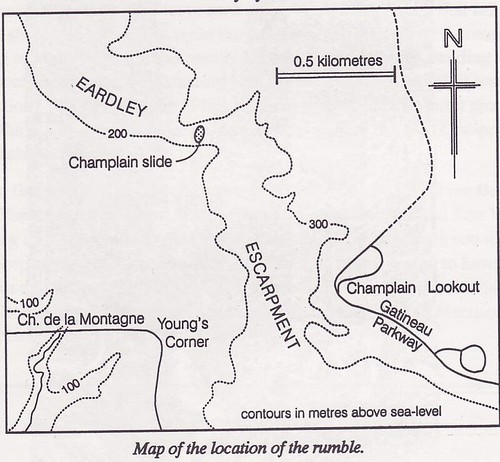

]]>If you stand at the Champlain Lookout you can see two things. One is a road stretching straight away westward toward the Ottawa River. Where that road meets the bottom of the cliffs below you is called Young’s Corner. Another thing you can see looking northwest along the face of the escarpment, is evidence of a rock-fall. It turns out this is just beyond Western Lodge. In the cold morning of April 1957 that rock-fall pretty much shook the residents around Young’s Corner right out of their beds.

In 1998 Don Hogarth wrote an article explaining why the Eardley Escarpment is falling down at this particular place. It turns out that about a billion years ago there was almost a volcanic explosion here. It smashed the older rock before new molten rock squirted into the cracks. The new rock was slightly water soluable and on that Spring morning fifty-odd years ago frost in the cracks was enough to bust the mountainside loose. Within a very short time this newly exposed rock had been cultivated by its natural fauna—rock climbers.

Don Hogarth has kindly given me permission to reproduce his article as it first appeared in The Ottawa Field Naturalist’s Club periodical Trail & Landscape April-June 1998. Here it is:

Rumblings in the Park

An explosion and related rock slide near

Champlain Lookout,a billion years apart.

Donald Hogarth

Department of Geology

University of Ottawa

Early one day, probably in April, 1957, residents of Young’s Corner beneath Champlain Lookout were awakened abruptly by a violent crash from the north and an accompanying earth tremor beneath them. Part of the Eardley Escarpment (see map) had come tumbling down and its face had taken on a new form. The timing of this event, which we will call the Champlain slide, is impossible to pinpoint, but it definitely postdates mid-August 1956, when the writer first explored the scarp, and it certainly predates late-April 1962, during his second visit, when large fresh blocks barred the way. Inquiry from the residents below, off Chemin de la Montagne, produced some additional information. Oh yes, they remembered it well. And who could forget being rudely shaken from his or her peaceful slumber at 4 a.m. one frosty spring morning “four or five years back.” Further precision is virtually impossible. Dr. David Forsyth, a seismologist with the Geological Survey of Canada, states that, with a minor tremor like this, by the time the shock had reached the Ottawa seismographs, it would be irretrievably intermingled with a myriad of other small shocks (including the effects of construction and traffic). The Gatineau earthquake would be hopelessly lost in the background.

Why did these rlocks choose this specific site to fail and this particular time to break loose? To answer these questions we must review a few scientific truths and go back many years in time.

Rocks of the Champlain slide and surroundings belong to the Wakefield batholith, an irregular body composed of igneous rock, that was emplaced as a molten mass at great depth, some 1,150 million years ago, and is now exposed over 110 square miles (or 70,000 acres or 28,000 hectares) of rolling countryside and much of Gatineau Park. In the immediate area, the predominant rock is syenite (like granite but lacking quartz), and less abundant granite pegmatite (a coarsegrained quartz-feldspar rock) and aplite (a rock of the same composition, but in sand-sized grains). All three are very hard and notably brittle.

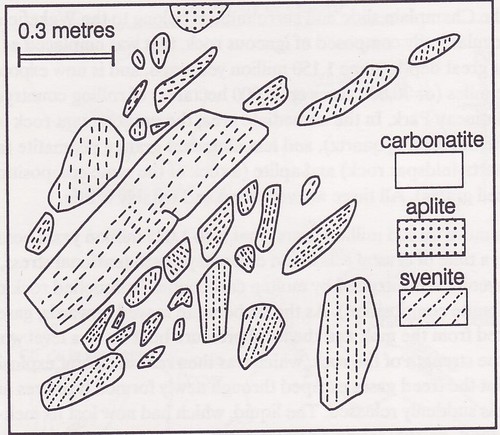

Let us now move on 125 million years (that is to 1,025 million years before present) to a time of crustal relaxation or perhaps even tensional stress, when solidified syenite was intruded by molten carbonatite (a liquefied rock of calcite-dolomite composition). As the carbonatite moved upwards, gases disassociated from the melt and the local pressure built up to a level where it exceeded the strength of the rock, which was then rent in violent explosion. At that point the freed gases escaped through newly formed fractures and the pressure was suddenly released. The liquid, which had now lost its melt -enhancing watery fluid, quickly solidified into a calcite-dolomite rock. In effect, the fractures were sealed with carbonatite. Thus an explosive breccia came into being here, a rock composed of coloured blocks and fragments of syenite, pegmatite and aplite, cemented with sheet-white carbonatite (see figure).

In the illustration, syenite fragments (clasts) are shown disorientated, one from the other. This is to be expected after a violent explosion, where the strata would be fragmented, disrupted and thoroughly mixed. One clast would be rotated one way, its neighbour another, resulting in a random orientation. This feature is shown by the alignment of dark minerals in the clasts (in the illustration). When the clasts came to rest they were glued in place by white carbonatite (unpattemed). In their new environment, the still-hot clasts reacted with the cement to produce a narrow rind (up to one centimeter thick) of blue amphibole and brown mica.

The Champlain slide exposes one of many explosive breccias in the southern part of the Wakefield Batholith, which include the floor ofPortune Lake and the benchmark point on NCC trail 36 at Hope Bay (Meech Lake). Such breccias in Gatineau Park are not new discoveries. They were described as sedimentary structures conglomerates by J. B. Mawdsley in 1930, but were re-interpreted, with a model similar to that outlined here, by R. Beland in 1952 (see “further reading and reference” at end of this paper). What is special about the rock at Champlain slide, is it’s three-dimensional aspect. Here we see a slice through the throat of the breccia pipe.

The breccia at Champlain slide, after a 1962 sketch of the side of one of the dislodged blocks. The contact between carbonatite and syenite (or aplite) is marked by a narrow reaction zone of mica and amphibo1e, omitted for simplicity. Patterns on syenite clasts indicate trends of dark minerals. Part of an aplite clast is shown near the top of the illustration, but granite pegmatite clasts do not appear in this restricted view.

Returning to geological events, the next chapter of note is the widespread initiation of brittle fracturing which took place throughout the Outaouais, 450 million years ago, or perhaps later. Along these fractures, the Ottawa Valley slice (which underlies the present Ottawa River and the municipalities of Ottawa, Gatineau, Hull and Aylmer) was enabled to subside several hundred metres, activated by sheer gravity, and resulting in the proto-Eardley Escarpment on its northern side. Por our purposes, this escarpment is important because it is defined by a steep face along which rocks can fail in rock slides. Today, the escarpment descends steeply, about 700 feet (200 metres), to the Ottawa River plain below.

Since the appearance of the Eardley Escarpment, the area has remained relatively stable. It is true that the Valley transects an active seismic wne at Ottawa, but shocks are minor and the turbulence associated with igneous activity is long since past. For the most part, after the Ordovician inundation (about 450 million years ago), the area has remained above sea level and exposed to the elements. Even during the brief post -glacial marine incursion (10,000 years ago) the site of the Champlain slide was 45 metres above the icy waters of the Champlain Sea. However, it was this very continental stability that, in the end, resulted in rock failure and land slide. The relatively high block horst of the Park was exposed to several hundred million years of continuous and unrelenting erosion. The softer and more-soluble carbonatite (with respect to syenite) was preferentially attacked. Over the years, water percolated through the somewhat permeable carbonatite and openings were enlarged by further solution. The rock became water saturated. Rock failure was probably triggered by springtime freeze-and-thaw. And then the roof came crashing down.

Today, the wall behind the slide is smooth, drab-gray and monotonous. Formerly it was almost white, interrupted by a narrow dyke of pink pegmatite running the length of the subvertical face, and by a layer of pink aplite at the top. The face showed a few carbonatite-sealed fractures but these were most evident in the huge blocks of dislodged rock at its base. Failure seems to have been most common along the contact of carbonatite and syenite or aplite, especially where these rocks had reacted to produce a coating of fine-grained amber mica or blue amphibole asbestos.

It is regrettable that weathering has obscured this spectacular geological site, but what nature has hidden in one place it will reveal in another. With lateral recession of the escarpment more carbonatites are bound to appear. But this process is time consuming, and few of us can afford to wait one or two hundred years for the next exposure.

Further reading and reference

- Baird, D. M. 1972, editor, Geology of the National Capital area. 24th International Geological Congress. Guidebook to Excursions B-23 to B-27. 32 pp.

- Beland, R. 1952 Le pseud<xonglom6rat du Lac Meach. Le Naturaliste Canadien 78:361-366.

- Hogarth, D. D. 1970. Geology of the southern part of Gatineau Park, National Capital region. Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 70-20. 8 pp., plus Map 7-1970.

- Mawdsley, J. B. 1930. The Meach Lake Conglomerate. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada 24:99-118

Last week I informed Gatineau Park lovers that the sound of rain they might be hearing in the woods was actually caterpillar droppings. This week I’ve heard from a number of people about the caterpillars including Kathy who told me there were so many on the parkway she could hear them squishing under her tires. So people are wondering, will this kill the trees? Is the NCC going to do anything?

I contacted the NCC and was given a copy (below) of the info that the people at the visitor centre are using to explain the situation to visitors. I also talked to Louis-René Sénéchal who explained some of the aspects of this phenomenon as you can hear in the video.

A couple of interesting notes: The scientific name of the Forest Tent Caterpillar is Malacosoma disstria. This name actually refers to the moth phase as opposed to the caterpillar. malacosoma means “soft body.” Here’s that moth:

Even more fun is the scientific name of the flies that Louis-René Sénéchal mentioned. These are called Sarcophaga aldrichi and that word Sarcophaga is from ancient Greek and related to our word sarcophagus which is what you might call the huge old stone coffins in which the Egyptian pharaohs were entombed. The Greeks chose a very special stone for the similar coffins they produced because they thought that that particular stone had the ability to eat the flesh of the dead. The words Sarcophaga and sarcophagus literally mean “flesh eating.”

For the sake of completeness here is what went into today’s video:

Kathy wrote:

Yesterday, we drove to the look off at the top of the Gatineau Park parkway with the intention of having a picnic at Étienne Brulé.

At first I though the trees looked strange. Then we noticed that we could hear the tires on the caterpillars on the road. There are caterpillars every where. They are eating the trees. It is very extensive. You cannot walk without stepping on them. We certainly didn’t eat there.

We continued down to Dunlop Field to have our picnic. We walked up the waterfall trail. There are a lot of caterpillars there but not as many. They are floating down the stream and are more prevalent on the small bridges ….. but it is abnormal.

Will there be any action taken? Will this kill the trees? Do you have any idea how long they will continue?

Louis-René Sénéchal sent me this briefing note.

I wrote back to Kathy:

Will action be taken?

Yes, I’ll do my weekly video on these little creepy things.

But I did talk to someone at Gatineau Park who tells me this is a 10 year cycle and is now at its peak. The trees can have their growth stunted in these years but it is unlikely to kill them. If it goes on too long (it often lasts 3 years, this is the 2nd) they can be weakened and more prone to other insect attack and infection.

But the good news is that people have also been complaining about a certain kind of fly that seems more abundant in the Park and it turns out that this kind of fly is parasitic and likes to be a parasite to tent caterpillars.

So, as gross as they are, my Gatineau Park contact finds them fascinating (or claims to) and hopes they can be some kind of tourist attraction while they last.

Isn’t nature wonderful? ![]()

Photo credits

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:East_tent_caterpillar_tent.jpg

http://imfc.cfl.scf.rncan.gc.ca/ins-images-eng.asp?geID=9374

http://twitpic.com/1qqwxe

]]>NOTE: this walk is offered this coming Sunday May 23, and again the following Sunday see here for details.

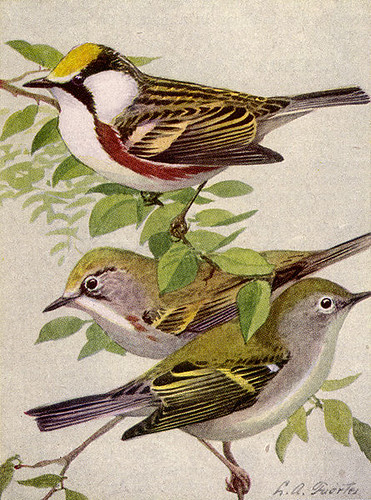

I joined about a dozen people who walked with Marie-Sophie Bourque around the Sugarbush Trail this past Sunday as she expounded on one of her favourite topics: birds. Before the walk—as is usual for these NCC interpretive events—we spent a little classroom time inside the visitor centre. It didn’t take long but Marie showed off a range of bird books from those aimed at the beginner to specialized tomes with a focus on one particular area of birding, such as nest identification or one specific family of birds. In particular she liked the Roger Tory Peterson Oiseaux du Québec et de l’est de l’Amérique Nord for which there is an accompanying audio disk. She likes it in part because she can look up a bird in French and the English name is there too, but since I’m likely to be sticking to English here also is the English equivalent book and CD. She also said she liked Thayers Birding Software, Brirds of North America and used it to show us something called the ovenbird.*

The ovenbird is called the ovenbird not because it is like a turkey that we might cook in our ovens, but because it builds a nest on the ground and that nest has a roof and a small round door. These reminded ornithologists of an earlier era of the domed shape of a village bread oven (there was a time when most houses didn’t have their own ovens but villages shared a common wood burning oven out in the village square).

The bird makes a call that is supposed to sound like petits pieds and Marie-Sophie played the song for us a few times so we would recognize it in the woods, then out we went.

Here’s a sample of the ovenbird’s song:

The first thing we saw was a crow perched on the sugarshack but no one passed comment on that. Instead we turned a small sea of binoculars down into the little Chelsea Creek to espy a pair of Canadian Geese and their two fuzzy goslings which Marie thought were early this year based on our particularly warm spring. We hadn’t even turned around before someone notices a turkey vulture soaring overhead.

But things actually got interesting when we reached the bridge because that’s where Marie showed why birders see more birds. The reason is because birders hear more birds. Who would know to even look for the almost microscopic Chestnut Sided Warbler? Only someone who knew its song and recognized its auditory presence before noticing any flitting between the leaves. And so we spent quite a while listening, pointing up into the leaves and describing to one another which branch to look for to see the tiny profile.

There are 230 species of birds represented in Gatineau Park which is fully half the number of species thought to inhabit Quebec. We didn’t get to see nearly that many. But what we missed in birds we made up for in caterpillars; the tent caterpillars are out with a vengeance. As we walked under the sunny canopy of leafy tree cover we could hear a gentle rain on the forest floor. A gentle rain? Actually it was the collective droppings of a zillion munching caterpillars up in the trees all pooping away as they busily defoliated.

About 10 minutes down the trail, just before it bends away from Chelsea Creek we noticed a Pileated woodpecker. They’re hard to miss; they’re pretty big. But wait, there were two! One went that way; the other one is still on that tree; no wait, it’s gone into that tree, see the hole? Yes there is a nesting pair of Pileated woodpeckers visible from the Sugarbush Trail. The tree is on the east side of Chelsea Creek (the trail being on the west side) in a large Aspen or Poplar tree. It has whitish bark so you could mistake it for a birch. The hole where the nest is located looks like a knot where a branch might have broken off about a third of the way down from the upper leafy branches.

A few paces down the trail Marie pricked up her ears to the song of a Rose breasted grosbeak. With its blood red marking high on its chest it looks quite striking. This one was right over our heads. This is the bird for which all the people in the video are craning their necks.

A few blue jays flew by and we talked about more than saw the Eastern Phoebe and similarly the Nuthatch but one of the younger birders espied once again a turkey vulture soaring over. Marie explained that it could be recognized even in profile by the fact that it didn’t flap its wings much but hung on them in a slight V position, frequently wobbling as it made adjustments. Our young and budding ornithologist then brought up the revolting means by which these birds are said to defend themselves—by barfing on their attackers. Marie responded by saying that the reason the beautiful things have no feathers on their heads is so that they can peck away at rotting flesh (they eat dead things) without getting their head feathers splattered in bacteria (yum).

At last we heard the song of the ovenbird, though we never did see the sneaky thing. Here Marie revealed her secret. Speaking for myself, one bird chirp—although not identical to another—is as unidentifiable as another. Yet Marie seemed to be able to identify each bird by its sound as easily as if she actually clapped eyes on it. How did she do that? The secret she told us, was that she practiced with only one at a time. That’s why she’d gotten us to listen to the ovenbird back in the Visitor Centre. She said you can never keep things straight if you are trying to remember several calls you don’t already know. The thing to do is to concentrate on one particular call. Get it memorized and then go out looking for that particular bird. After a few times that special one will become second nature to you and you can try for another.

We had heard an indigo bunting (above) and so went searching for it in an open space near the end of the trail. At first there was no sign of it and then it appeared. Unfortunately not long enough for me to actually see it though. As we strolled back on the last few steps of the trail one of our company told the story of an evening grosbeak. Evidently, when our storyteller was a child, her mother had found a colourful bird seemingly helpless in the middle of the road. She’d gone to each of the neigbour’s houses asking if they’d lost a bird. It looked so pretty she thought it must be a pet. Finally they took it to the humane society where the official identified it as an evening grosbeak and diagnosed its inability to fly as being the symptoms of having eaten fermented berries and being drunk. Accordingly after a night in the basement wobbling unsteadily on an indoor clothesline the bird was released to fly away with only a suspected hangover.

*Rachel at the NCC has sought out the source for Thayers Birding Software, Brirds of North America

the Wild bird unlimited Nature Shop

Blue Heron Mall,

1500 Bank Street

Ottawa, ON K1H 7Z1

Phone: (613) 521-7333

http://www.yogaretreats.ie/oven.htm

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Branta_canadensis_juv.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turkey_Vulture_(Cathartes_aura)_-in_flight.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pileated_Woodpecker_in_a_Tree.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rose-breasted_Grosbeak.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IndigoBuntingonPlant.jpg

]]>The Lauriault Trail is a benign little hike. Who would suspect that it commemorates a killer?

Actually it wasn’t Jean-Baptist Lauriault who was the killer. It was a hill on the Kingsmere Road that was the killer. Today there is no official trail or road connecting the Kingsmere Road to the Champlain Parkway so it’s hard to realize that the Lauriault Trail parking lot is only a stone’s throw from the south-western tip of Kingsmere Lake.

Before the parkways were built, in a time when farmers were scratching out a living from these rocks, one of the ways they used to travel in to town or to visit their neighbours was down an extension of the Kingsmere Road which dropped more than 200 meters over the face of the escarpment. This was known as Lauriault’s Hill and it was steep enough to kill people.

People and horses too, because when the road was cut there were no cars. The hill was said to require four horses to pull a wagon up it. Imagine trying to go down. Imagine trying to down on ice in winter.

Katherine Fletcher’s book Historical Walks says there was once a sign on the road warning that 13 people had been killed.

Dr. T. B. Davies, coroner of Hull called it “the most dangerous hill in Ottawa district.”

When cars did arrive on the scene they spawned a story that Lauriault’s Hill was so steep that your Model-T Ford could only be driven up by going in reverse. Evidently going front first tilted the engine above the level of the gas tank and since the fuel was gravity fed this stalled the engine.

All that ended in 1957 when the new parkway was put through and Lauriault’s Hill was closed.

]]>Next time you’re at Mulvihill Lake here’s a story to tell your friends.

Mulvihill Lake is in Gatineau Park along the Champlain Parkway just half a kilometer beyond the parking lot below the MacKenzie King estate.

The Mulvihills moved into the Ottawa area in 1828, at least John Mulvihill did. He was attached to the military regiment stationed here. That was the 100th Regiment. Mulvihill wasn’t actually in the army he was a clerk during the time that John By was building the Rideau Canal, the construction of which was a military operation that began in 1826. Evidently John Mulvihill leased property from Colonel By in a location which is just about where the US Embassy stands today in downtown Ottawa. But none of this has anything to do with Gatineau Park or Mulvihill Lake.

It was John’s son Phillip who bought the property where Mulvihill Lake now lies. He bought it from from Jean-Baptiste Lauriault, Lariault being a name also visible on the signs around the trails near Mulvihill Lake.

Though you can’t easily tell when you’re on the ground, this area lies just below Kingsmere Lake; it’s the houses at Kingsmere you can see through the trees.

The niche in which the lake lies was once known as “The Hollow.” By this people meant a hollow in the hills of the Eardley Escarpment but the place was made even more of a hollow because at first there was no lake where Mulvihill Lake now lies.

In 1948 or ‘49 Basil (or Bud) Mulvihill brought in a bulldozer and hollowed out the earth to create the thing!

You might expect that someone would object to digging an artificial lake in Gatineau Park, but of course at the time this wasn’t part of the park. Someone did object though and that someone was William Lyon MacKenzie King. His big beef was that this artificial lake was cutting off part of the water supply to his beloved Bridal Veil Falls.

What’s a prime minister to do? Sue of course. Except Basil Mulvihill had something on his side; time. MacKenzie King died only a year later so his lawsuit never made it to court.

But Mulvihill Lake wasn’t finished with MacKenzie King yet. MacKenzie King loved his walk down to the falls and had the path widened and stone bridges built. Mulvihill Lake was trapped behind an earthen dam and in 1953 that dam broke sending a minor tidal wave of muddy water shooting down the hill to wash out MacKenzie King’s stone bridges.

Evidently for a while Mulvihill Lake was stocked with trout and people went fishing there. Now there is an observation platform out over the water where you can watch the frogs and minnows.

UPDATE: I now understand that the “observation platform” at Mulvihill Lake was installed in 1977 specifically as a place for wheelchair accessible fishing and that the stocking with trout was done to serve this purpose, but due to the shallowness of the lake, re-stocking needed to be done each year because the fish couldn’t survive when the lake temperature rose during the summers.

]]>One of the more modest trails in Gatineau Park is dedicated to the first European pioneers who settled in the region.

I t was 1800 when Philemon Wright brought a small group of families from Massachusetts and set up shop where downtown Gatineau stands today. The next year Samuel Ezra Benedict was tempted up from New York to start farming the 150 acres over which this trail traces a tiny fraction. For the purpose of the trail the Benedicts are a proxy for all the other pioneers who settled here two centuries ago.

t was 1800 when Philemon Wright brought a small group of families from Massachusetts and set up shop where downtown Gatineau stands today. The next year Samuel Ezra Benedict was tempted up from New York to start farming the 150 acres over which this trail traces a tiny fraction. For the purpose of the trail the Benedicts are a proxy for all the other pioneers who settled here two centuries ago.

The trail starts near P3 and the Welcome Centre (lowest red arrow on the map below) and is laid out to emphasize the fact that although many think of Gatineau Park as a pristine wilderness, the land has been intensively used for decades and some of the wilderness we see is relatively recent growth.

Although one of the interpretive signs claims that some of the oldest trees along the trail were standing when Benedict arrived to found his farmstead, this seems a bit unlikely. Such 210+ year old trees would have begun in a mature pine forest and had to survive not only 150 years of farming but also the great fire of 1870 which devastated the area. Another one of the signs points out that the farmers often cut timber on their land and sold it to make some money.

Still, the point is true that various stages of the walk bring the visitor through various stages of the forest reestablishing itself and gives you a chance to identify various species of trees at close range.

The trail is wheelchair accessible and only 1.3 kilometers long. Nowhere is it steep. It is a little dated though. The signage refers to the city of Hull which changed its name to Gatineau in 2002.

The Benedict farm actually stretched well east of the pioneer trail and into the citified part of the City of Gatineau. The northern edge was where Mont Bleu Boulevard is now (uppermost red arrow). The farmers depicted in the interpretive sign weren’t actually the Benedicts, nor is the house shown behind the plowman their house.

The Benedict farm actually stretched well east of the pioneer trail and into the citified part of the City of Gatineau. The northern edge was where Mont Bleu Boulevard is now (uppermost red arrow). The farmers depicted in the interpretive sign weren’t actually the Benedicts, nor is the house shown behind the plowman their house.

When they first arrived they cleared the land and used some of the logs of the pine forest to build a log cabin. By the 1860s the family was prosperous enough that they built one of the first stone homes in South Hull; it had 10 rooms and nine foot ceilings and is still standing today. Here it is in 1940 and again in the more recent past (click either to enlarge).

But you can’t see it in Gatineau Park. As I said, the farm was 150 acres and the house is actually fairly far away from the Pioneers Trail. It’s in among a bunch of other houses on a shady street north of Saint Raymond and east of Cite-des-Jeunes. The leftmost arrow shows the location.

The farm was a going concern until the 1950s when it was sold in part to make way for houses and in part to make way for the then new Gatineau Parkway.

As the city encroached on the farm it left its mark before houses started popping up. By the 1930s the farm was registered as Town Site Farm.

Getting back to the Pioneers Trail: the trees identified as being along the trail are butternut, linden*, sugar maple*, beech*, ironwood*, rum cherry*, birch*, aspen*, and white ash*. Only those with asterisks have any interpretive information on the signs though.

Linden – Tilia americana (Wikipedia link)

Sugar Maple – Acer saccharum (Wikipedia link)

Beech – Fagus grandifolia (Wikipedia link)

Ironwood – Ostrya virginiana (Wikipedia link)

Rum Cherry - Prunus serotina (Wikipedia link)

Birch – Betula papyrifera (Wikipedia link)

Aspen – Populus tremuloides (Wikipedia link)

White Ash – Fraxinus americana (Wikipedia link)

]]>So some weeks ago the Ecosystem Conservation Plan came out. It got press because it had rock climbers up in arms. But other users are also going to be impacted and GuideGatineau gave critical comment calling on the NCC to come through with their purported desire to be open and transparent, specifically by engaging in more two way discussions with the climbers and with other park users.

Later I got picky about how there seemed to be little action in the action plan when it came to climate change and again challenged the NCC to aim higher.

And other people have other complaints about the Plan.

But that doesn’t mean that the general direction is a bad one. Keeping the park natural and healthy is something that everyone wants and that’s what the NCC wants to do too.

Part of that job is to communicate conservation to people and so the NCC wants to use the most effective message. Louis René Sénéchal works for the NCC and asked if I’d let GuideGatineau users help by brainstorming on that messaging. In this video he says:

“I want the input from park users to provide me with ideas for a catchphrase, a tagline, that would in a few words summarize the intention of the Conservation Plan. [It needs to] provide a feeling of a fine balance between people belonging in the Park and the Park belonging to the plants and animals that live in it. We have lots and lots of users in the park. The vast majority of users come in with the intention of leaving little or no trace. The protection of the Park is everybody’s business. [One French tagline we like is] “protéger le parc, une visite a la fois”; it does call for action, it says to the users take a look at what you’re doing every time you come in and that way you will be able to part of the long term survival of the Park. It’s really everybody’s business to protect the Park.”

“I want the input from park users to provide me with ideas for a catchphrase, a tagline, that would in a few words summarize the intention of the Conservation Plan. [It needs to] provide a feeling of a fine balance between people belonging in the Park and the Park belonging to the plants and animals that live in it. We have lots and lots of users in the park. The vast majority of users come in with the intention of leaving little or no trace. The protection of the Park is everybody’s business. [One French tagline we like is] “protéger le parc, une visite a la fois”; it does call for action, it says to the users take a look at what you’re doing every time you come in and that way you will be able to part of the long term survival of the Park. It’s really everybody’s business to protect the Park.”

The video also contains a few people tossing out brainstorming suggestions, including:

- Ours to enjoy, ours to protect

- Respect it for future generations

- We need to preserve our precious gem

I might add

- Protected, naturally

- Visit what lives here

- Protect it one visit at a time

Please us the space below to toss in your suggestion, or email me directly. All suggestions will posted (that’s what stimulates the brainstorm). Satirical or cynical posts will be posted too but redirected here instead.

]]>